Die Kasseler Liste is a growing database that presently comprises 125,000 data sets. It documents the global scale of censorship. Book bans persist across the world, on all continents, with varying reach and intensity, depending on political and social contexts.

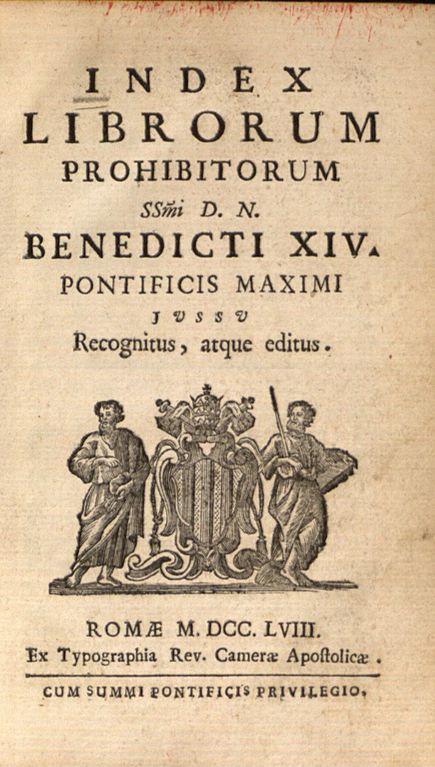

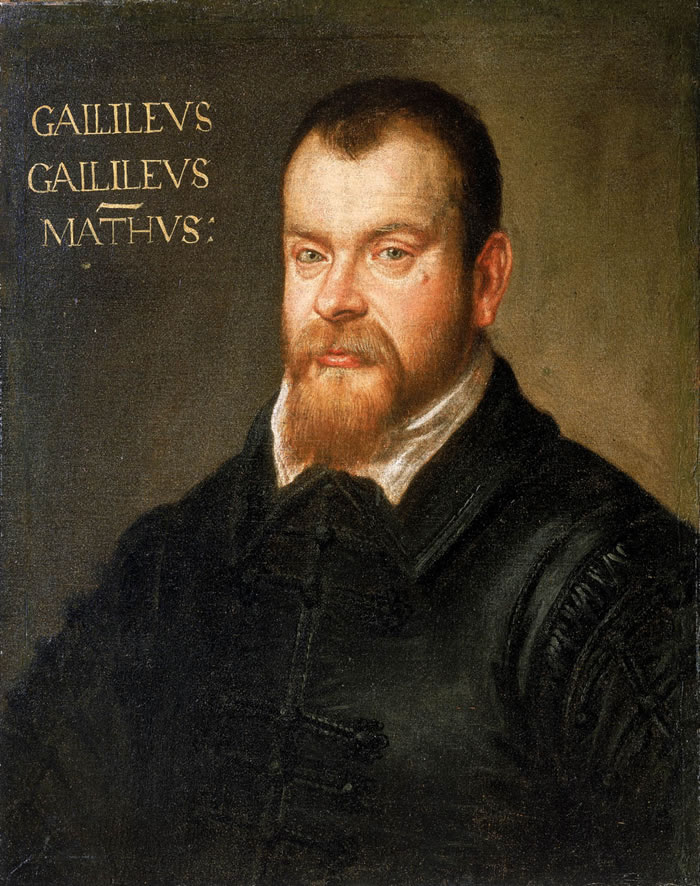

Die Kasseler Liste covers vast territories and a large time frame. The earliest entries are taken from the „Index Librorum Prohibitorum,” which the catholic church first published in 1559 and which is represented in the database in its final version from 1948. It is but one example for censorship originating not only from government institutions. Civil and religious institutions similarly have their own history of systematically infringing on the right to freedom of expression. The Catholic lay organization Opus Dei, also featured in Die Kasseler Liste, is another case in point, where rigid and coercive reading directions provide the members with a tiered index. On the other hand, school districts and school libraries in the United States of America also have a record of systematically banning books from their collections.

Historical indexes are an important component of Die Kasseler Liste. Whenever possible, they are reproduced in their entirety, such as the “Liste des schädlichen und underwünschten Schrifttums” of the Third Reich and the “Liste der auszusondernden Literature” in the Soviet Occupation Zone and later in the GDR (1946–1953), but also the current index of Opus Dei (i.e. the books listed therein with a ‘prohibition grade’ between 3 and 6).

However, censorship doesn’t always result in lists of banned books, with good reason. On the one hand, states that engage in censorship often want to seem unpredictable in their actions, and an official list would run contrary to this goal. Censorship is often arbitrary and illogical, depending on the current political climate, and it thus creates a permanently threatening atmosphere. On the other hand, and index openly acknowledges the fact that the state is indeed engaged in censorship. Naturally, restrictive states that are officially free of censorship will avoid such an acknowledgement.

To document censorship in those contexts where indexes don’t exist, Die Kasseler Liste often relies on other publicly available databases. Zensur in Österreich 1750–1848, for instance, the vast database curated by the University of Vienna since 1999, contributed a large number of datasets to the List of Banned Books, as did the collection on books banned in Texan prisons, published by the Texas Civil Rights Project. But of course, many parts of the world lack academic or civil institutions that would document the history of censorship in the respective region. In these cases, the entries in Die Kasseler Liste are the work of individual researchers. This activity costs the most time and energy yet yields the fewest results. Exhaustive reports are impossible, and the entries should rather be considered as examples. In this sense, censorship under the dictatorial regimes of Spain, Portugal, Greece, East Germany, the Soviet Union, Argentina, Chile or South Africa in the twentieth century is documented through selected cases of prohibition. Similarly, official book bans from the recent past in China, Russia, Malawi, Turkey or New Zealand are subject to such exemplary investigations which, within the scope of such a project, can never aspire to completeness.

Its global outlook notwithstanding, the focus of Die Kasseler Liste lies on germanophone literature. This is due to the location of the project and its collaborators as well as the comprehensive lists of censored books that exist for Europe’s German-speaking territories. The asterisk in our database (*) is reserved for titles from the “Liste der auszusondernden Literatur” issued after World War II in the Soviet Occupation Zone which predominantly features national socialist literature. These items were not part of the installation The Parthenon of Books.

Censorship is a phenomenon where one generally perceives but the tip of the iceberg. Oftentimes the process cannot be linked to specific book titles, as states with particularly tight restrictions on freedom of expression resist admitting the same. Even more difficult to trace are practices of self-censorship: One will never know which books were not written due to fear or experiences of repression. In this sense, too, the project Die Kasseler Liste is as incomplete as it is interminable.

This disparate and snippet-like mapping of censorship across the world, past and present, simply reflects the evolving nature of the project Die Kasseler Liste. In no way does this tentative map imply that countries not named above are or have been free of censorship – at best, it means that their history of censorship has yet to be fully explored.

Die Kasseler Liste contains not only geographical gaps; oftentimes it was not possible to collect complete data sets. Some imported lists, for example, lacked information on the place of publication. It would not be impossible to fill these fields with data, but it would require a lot of additional resources. A scientific database such as the one produced by the team behind Zensur in Österreich requires considerable time and funding.

The ‘source’ column equally contains gaps. The category ‘individual research,’ for instance, indicates that one of our team members to the best of their knowledge completed a through investigation to unearth a single title. These results, however, cannot be considered ‘academic’ in the proper sense, as they rely on data that is not always scientifically verifiable, such as oral testimony. Yet this is precisely what censorship seeks to achieve – to become untraceable. The explicit, scientifically verifiable lists of censored books are the exception from the rule, the tip of the iceberg. In this sense, items listed under the category ‘individual research’ represent explorations below the water surface, so to speak.

All these things considered, Die Kasseler Liste should be understood as a bold experiment, a first beginning, a tessera that will eventually become part of a comprehensive documentation of censorship across the world.